Dubai’s Best Lawyers: Delivering Excellence in Every Case.

Our Dubai-based lawyers provide clear, pragmatic, and bespoke advice, drawing on extensive experience and strategic insight to deliver outstanding legal services.

LYLAW provides legal expertise you can rely on.

Legal matters significantly affect your personal and business well-being, making it crucial to ensure that your interests are always prioritized with tailored advice and comprehensive solutions drawn from extensive experience in the U.A.E.

Client-focused law guidance for businesses.

Our straightforward legal services with no hidden surprises.

For over 15 years, we’ve been helping clients navigate their legal challenges.

Meet the LYLAW team

Lawgical with Ludmila

Understanding U.A.E. Law: Articles & Insights

Why clients rely on LYLAW

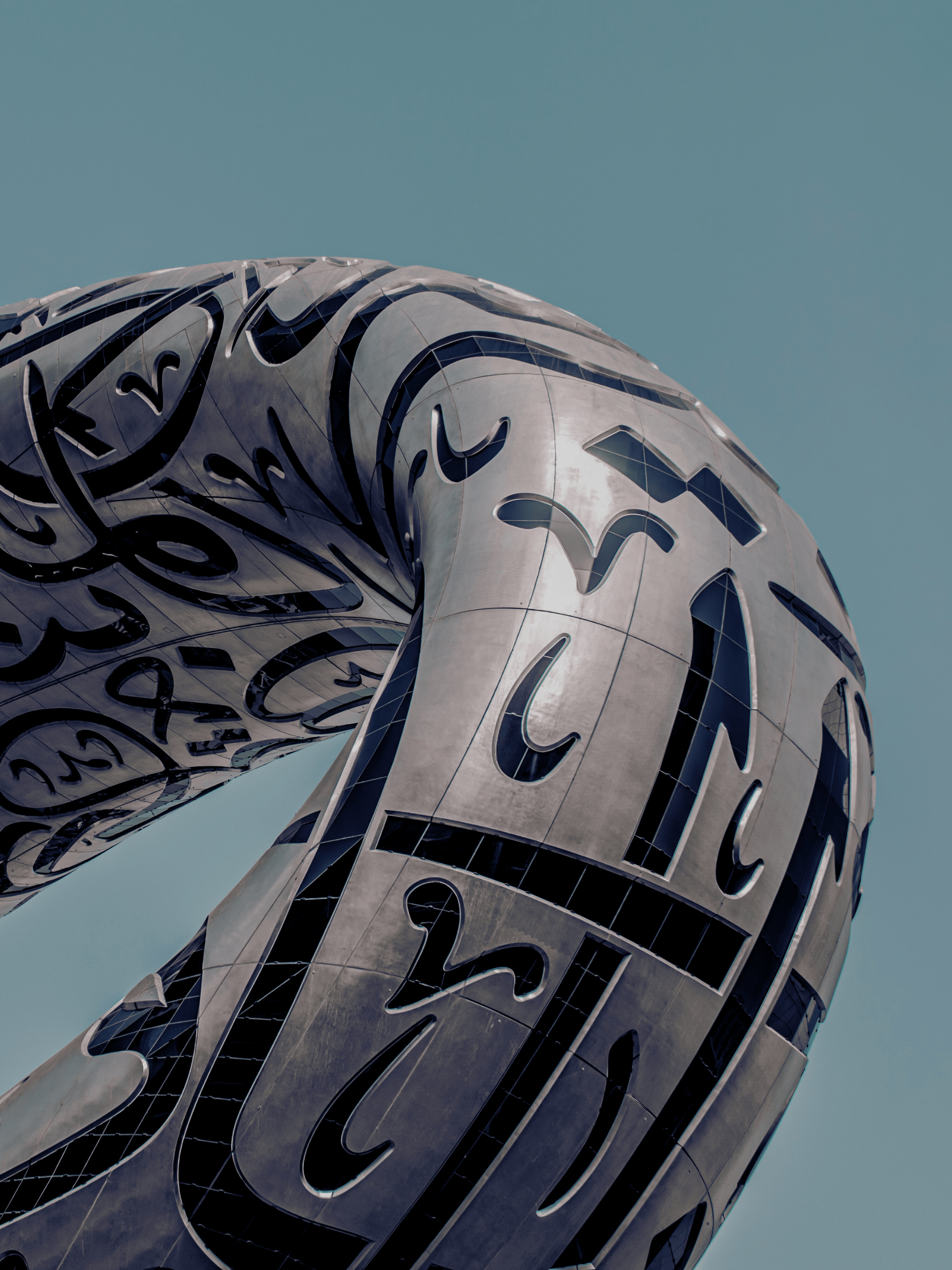

Discover our Dubai location

Get Expert Legal Guidance You Can Trust

FAQ about LYLAW

Is HPL Yamalova & Plewka FZCO also the name of your law firm?

Yes. HPL Yamalova & Plewka FZCO is the firm’s official legal trade name. It is the name under which the firm is licensed, regulated, and publicly recognized by the relevant authorities. The firm also operates under the brand name LYLAW, which is used for branding and communications purposes

Why is it important to hire lawyers in Dubai for legal matters?

Utilizing lawyer services in Dubai can be invaluable for individuals and businesses involved in complex legal matters or disputes. By working with a top law firm in Dubai, you’ll have access to professional legal counsel, empowering you with the confidence to navigate U.A.E laws stress-free.

Experienced legal firms in Dubai provide clients with critical support in a range of areas, such as drafting contracts, resolving disputes, and representing you in legal proceedings to safeguard your rights.

How do I choose the best lawyers in Dubai?

Choosing the best lawyers in the U.A.E. and Dubai all comes down to evaluating their experience, expertise in relevant practice areas, and reputation. Look for a legal firm with a strong track record, excellent client reviews, and a deep understanding of U.A.E laws. At LY Lawyers, we combine our legal consultancy service with a client-focused approach to deliver tailored solutions for your legal needs.

What types of legal services does your firm offer?

We are a general practice law firm offering a wide range of legal services to meet the needs of individuals, families, and businesses. Our team handles matters across multiple areas of law, including civil, criminal, family, business, and estate-related issues. For a full list of the services we provide, please visit our practice areas page.

Does your firm offer legal services throughout the U.A.E.?

We handle legal cases throughout the U.A.E., directly and indirectly. We work closely with our long-standing and close-knit network of local advocates. Our firm is licensed as a legal consultancy by the Government Legal Affairs Department of Dubai (Ruler’s Court). The firm is managed by a U.S. qualified attorney, licensed by the California State Bar, Ms. Ludmila Yamalova. We are also registered and licensed by the Dubai Multi Commodity Center Authority (DMCC) and the Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) Courts. Our expertise and relationships allow us to effectively manage a broad range of legal matters, providing comprehensive legal services throughout the U.A.E.

How will I be kept informed about my case?

Our lawyers in Dubai will keep you informed through regular updates and clear communications, providing timely progress reports and answering any questions you may have throughout the legal process.

Does your law firm offer legal services in languages other than English?

Our multilingual team is proficient in Russian, Ukrainian, Arabic, French, and several other languages, ensuring we can provide comprehensive legal support and clear communication to clients from various linguistic backgrounds.

.svg)